Il Campione

The disrupted 2020 season saw the Tour de France moved from its traditional, familiar 3 weeks in July to a Grand Depart which took place in late August. In doing so, the race – and its followers – lost an opportunity to not only commemorate the 25th anniversary of arguably its darkest day in the modern era, but also to remember a champion whose life and career were cut tragically short.

Limoges, 21 July 1995: After more than 3 hours and 47 minutes of racing, the figure in the blue and red colours of the Motorola team zips up his jersey and begins the final few hundred metres of what is now an assured victory. The nearest rider is over 30 seconds adrift and the peloton is nearly 8 minutes further behind so Lance Armstrong is alone on the road, save naturally for the procession of commissaires’ vehicles and race motorcycles following him home. He takes both hands off the bars as he coasts in, raising skywards first his right index finger and then both before clenching both fists in a victory salute. A final stomp on the pedals and a glance over his left shoulder reassure him of his victory and, again, the fingers point on final time to Heaven, dedicating his win to his absent teammate.

Three days previously had witnessed the Queen Stage of the 1995 Tour de France; a brutal 207km chase from Saint-Girons that saw the riders tackle the Col de Portet d'Aspet, the Col de Menté, the Peyresourde, the Aspin, the Tourmalet before a final ascent to Cauterets. As far as a Tour’s Greatest Hits album might go, this stage alone would be a contender for at least one volume.

Richard Virenque had attacked at the foot of that first climb, less than 30km into the stage and would ultimately solo to victory, leaving chaos in his wake. In the ensuing chase a series of crashes occurred on the descent of the Portet d'Aspet where the road switched quickly from a right- to a left-hand bend. While most riders were able to remount with or without mechanical assistance, one figure remained motionless on the right side of the road, curled in a foetal position beside the concrete blocks which had halted his slide across the asphalt. The TV helicopter cameras lingered on the scene for the longest time. Too long.

Fabio Casartelli was more than just the last rider to lose his life in cycling’s most prestigious race. Born in Como in 1970, and like many Italians, he was a passionate cyclist who dreamed of being a professional. He showed promise in the domestic Italiam amateur scene, winning at aged 19 the 1990 Trofeo Sironi while following year saw no fewer than 5 one-day victories. These included the GP Capodarco, a race which would be won some 15 years later by a certain Jai Hindley.

Five more victories followed in 1992 before Fabio was selected to be part of the 18-strong (including 4 women) Italian cycling team for that year’s Olympic games in Barcelona. This, remember, was still an era in which many sports only permitted amateur athletes to compete in the jewel in sport’s crown. Fabio would join Mirco Gualdi and Davide Rebellin to contest the 195km men’s road race.

As Andy McGrath notes in Rouleur 18.4, the 3-rider format made the race unpredictable and difficult to control. Under a merciless Catalan sun, 3 riders eventually broke away: Dutchman Erik Dekker, Dainis Ozols from Latvia and Fabio.

As the race entered its final few kilometers, the trio had maintained a gap of around a minute on the chasing pack; a gap that began to tumble as the peloton hunted down medals. After more than 4 and a half hours’ racing, and with around 400 metres left to go, Ozols is forced to begin the lead out, Dekker and Fabio immediately leeching onto his wheel as they fight to sort out the medals. They snake first to the left of the road and then to the right, Ozols following the bend and trying to remain close to the barriers.

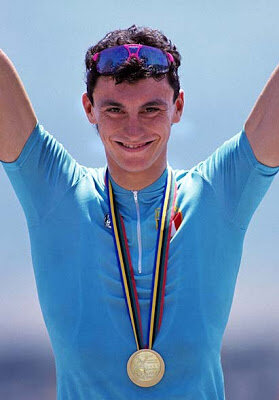

Two hundred metres to go. Ozols swings left again, glancing nervously over his shoulder before weaving lazily in an attempt to force the others to the front. Fabio takes the bait. He explodes off the Latvian’s wheel and dives right, head-down and stomping on the pedals. Dekker follows but with only 75 metres left, the wheel has gone, and the winner is now decided. Ozols has already sat up to celebrate his bronze medal and soon after the Dutchman also punches the air before Fabio himself finally sits up and raises both arms wide to the sky as he takes gold. The bunch followed some 35 seconds behind.

Like his teammate Davide Rebellin and silver medalist Dekker, Fabio turned professional after Barcelona. Fabio joined Giancarlo Ferretti’s Ariostea Team for 1993 and, while injury would be a constant feature of his first 2 years, the promise of Barcelona was visible. He finished in the top 10 on 4 stages of his debut Giro d’Italia (on the way to 107th on GC) and was denied stage victories by no lesser figures than Johan Museeuw and Viatcheslav Ekimov in the Tour de Suisse.

Ariostea folded at the end of the season and Fabio would ride for the ZG Mobili in 1994, the team managed by Gianni Savio. It would be a frustrating year with no repeat of the previous season’s highlights. After abandoning the Tour de France on Stage 7, the Italian’s season would culminate in surgery to cure recurring tendinitis.

Hopeful of a return to fitness and form following surgery, Fabio moved once more – this time to the US Motorola team, alongside countryman Andrea Peron, Canadian Steve Bauer and 1993 World Champion and Tour de France stage winner, Lance Armstrong.

Steady, if unremarkable, placings in the 1995 Dauphiné Libéré and Tour de Suisse provided some confidence that Fabio could get through multi-day races. Encouragingly, he was mixing it with the other fast men in the final of sprint stages in both races.

The 1995 Tour de France began in Saint Brieuc, Brittany and wended a clockwise route around the Channel coast and into the Classics terrain of Belgium. After a week of racing the race transferred to the Alps and would then trace a route through the Pyrenees before traversing western and central France to its now traditional finish on the Champs-Élysées. It had been an indifferent Tour for the Motorola team. Sixth in the Team Time Trial (nearly 2 minutes adrift of the victorious Gewiss – Ballan team) and a couple of top 10 placings for Frankie Andreu were about as good as it had been for the American team before a tactical blunder saw Lance Armstrong held off on the line in Revel by Serhiy Ushakov on stage 13. As the teams headed for the second rest day after stage 14, the highest-placed Motorola rider in GC was Colombian Alvaro Mejia some 26 minutes adrift of Miguel Indurain who was on his way to a fifth Tour victory in as many years.

The Fabio Casartelli Memorial, Col de Portet d’Aspet

Fabio’s death on stage 15 could have been a watershed for safety in professional cycling, not only rider protection (the compulsory wearing of helmets would be a further 8 years away, and in the aftermath of the death of Andrei Kivilev after a crash in the 2003 Paris-Nice) but also course safety. The concrete blocks designed to prevent vehicles plunging over the edge of the Col de Porte d’Aspet also contributed directly to the catastrophic head injuries that Fabio sustained. In some respects, the refusal to address both issues at the time also robbed Fabio of some fitting legacy to the sport he loved.

To some, he may simply be a tragic figure or the invisible team-mate of Lance Armstrong on the road to Limoges. To many others, though, Fabio will remain the grinning young man in the Azure jersey, sunglasses perched atop his ruffled dark hair and a gold medal hanging from his neck. Campione Olympico.

Footnote: Fabio Casartelli would have turned 50 on 16 August 2020. By a twist of fate, Il Lombardia, the one-day Classic which finishes in Castartelli’s hometown of Como, took place the day before. On the steep, fast descent of the Muro di Sormano, Deceuninck - Quick-Step rider Remo Evenepoel misjudged a tight left-hand bend and collided with a low stone wall on a bridge. The impact ejected the young Belgian over the wall and into the ravine below. As medics made their way to attend to the rider lying still in a near recovery position, the cycling world once again held its breath.