The Long Read

A deeper dive into professional cycling

Il Campione

The disrupted 2020 season saw the Tour de France moved from its traditional, familiar 3 weeks in July to a Grand Depart which took place in late August. In doing so, the race – and its followers – lost an opportunity to not only commemorate the 25th anniversary of arguably its darkest day in the modern era, but also to remember a champion whose life and career were cut tragically short.

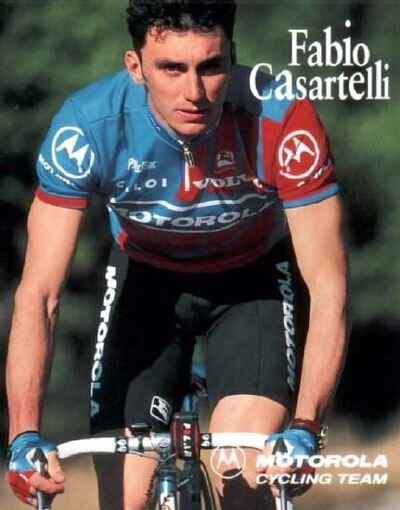

Limoges, 21 July 1995: After more than 3 hours and 47 minutes of racing, the figure in the blue and red colours of the Motorola team zips up his jersey and begins the final few hundred metres of what is now an assured victory. The nearest rider is over 30 seconds adrift and the peloton is nearly 8 minutes further behind so Lance Armstrong is alone on the road, save naturally for the procession of commissaires’ vehicles and race motorcycles following him home. He takes both hands off the bars as he coasts in, raising skywards first his right index finger and then both before clenching both fists in a victory salute. A final stomp on the pedals and a glance over his left shoulder reassure him of his victory and, again, the fingers point on final time to Heaven, dedicating his win to his absent teammate.

Three days previously had witnessed the Queen Stage of the 1995 Tour de France; a brutal 207km chase from Saint-Girons that saw the riders tackle the Col de Portet d'Aspet, the Col de Menté, the Peyresourde, the Aspin, the Tourmalet before a final ascent to Cauterets. As far as a Tour’s Greatest Hits album might go, this stage alone would be a contender for at least one volume.

Richard Virenque had attacked at the foot of that first climb, less than 30km into the stage and would ultimately solo to victory, leaving chaos in his wake. In the ensuing chase a series of crashes occurred on the descent of the Portet d'Aspet where the road switched quickly from a right- to a left-hand bend. While most riders were able to remount with or without mechanical assistance, one figure remained motionless on the right side of the road, curled in a foetal position beside the concrete blocks which had halted his slide across the asphalt. The TV helicopter cameras lingered on the scene for the longest time. Too long.

Fabio Casartelli was more than just the last rider to lose his life in cycling’s most prestigious race. Born in Como in 1970, and like many Italians, he was a passionate cyclist who dreamed of being a professional. He showed promise in the domestic Italiam amateur scene, winning at aged 19 the 1990 Trofeo Sironi while following year saw no fewer than 5 one-day victories. These included the GP Capodarco, a race which would be won some 15 years later by a certain Jai Hindley.

Five more victories followed in 1992 before Fabio was selected to be part of the 18-strong (including 4 women) Italian cycling team for that year’s Olympic games in Barcelona. This, remember, was still an era in which many sports only permitted amateur athletes to compete in the jewel in sport’s crown. Fabio would join Mirco Gualdi and Davide Rebellin to contest the 195km men’s road race.

As Andy McGrath notes in Rouleur 18.4, the 3-rider format made the race unpredictable and difficult to control. Under a merciless Catalan sun, 3 riders eventually broke away: Dutchman Erik Dekker, Dainis Ozols from Latvia and Fabio.

As the race entered its final few kilometers, the trio had maintained a gap of around a minute on the chasing pack; a gap that began to tumble as the peloton hunted down medals. After more than 4 and a half hours’ racing, and with around 400 metres left to go, Ozols is forced to begin the lead out, Dekker and Fabio immediately leeching onto his wheel as they fight to sort out the medals. They snake first to the left of the road and then to the right, Ozols following the bend and trying to remain close to the barriers.

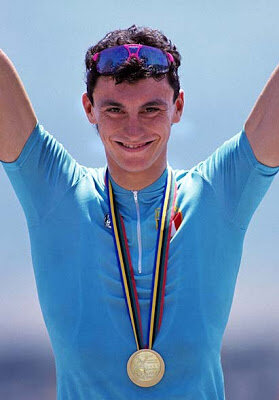

Two hundred metres to go. Ozols swings left again, glancing nervously over his shoulder before weaving lazily in an attempt to force the others to the front. Fabio takes the bait. He explodes off the Latvian’s wheel and dives right, head-down and stomping on the pedals. Dekker follows but with only 75 metres left, the wheel has gone, and the winner is now decided. Ozols has already sat up to celebrate his bronze medal and soon after the Dutchman also punches the air before Fabio himself finally sits up and raises both arms wide to the sky as he takes gold. The bunch followed some 35 seconds behind.

Like his teammate Davide Rebellin and silver medalist Dekker, Fabio turned professional after Barcelona. Fabio joined Giancarlo Ferretti’s Ariostea Team for 1993 and, while injury would be a constant feature of his first 2 years, the promise of Barcelona was visible. He finished in the top 10 on 4 stages of his debut Giro d’Italia (on the way to 107th on GC) and was denied stage victories by no lesser figures than Johan Museeuw and Viatcheslav Ekimov in the Tour de Suisse.

Ariostea folded at the end of the season and Fabio would ride for the ZG Mobili in 1994, the team managed by Gianni Savio. It would be a frustrating year with no repeat of the previous season’s highlights. After abandoning the Tour de France on Stage 7, the Italian’s season would culminate in surgery to cure recurring tendinitis.

Hopeful of a return to fitness and form following surgery, Fabio moved once more – this time to the US Motorola team, alongside countryman Andrea Peron, Canadian Steve Bauer and 1993 World Champion and Tour de France stage winner, Lance Armstrong.

Steady, if unremarkable, placings in the 1995 Dauphiné Libéré and Tour de Suisse provided some confidence that Fabio could get through multi-day races. Encouragingly, he was mixing it with the other fast men in the final of sprint stages in both races.

The 1995 Tour de France began in Saint Brieuc, Brittany and wended a clockwise route around the Channel coast and into the Classics terrain of Belgium. After a week of racing the race transferred to the Alps and would then trace a route through the Pyrenees before traversing western and central France to its now traditional finish on the Champs-Élysées. It had been an indifferent Tour for the Motorola team. Sixth in the Team Time Trial (nearly 2 minutes adrift of the victorious Gewiss – Ballan team) and a couple of top 10 placings for Frankie Andreu were about as good as it had been for the American team before a tactical blunder saw Lance Armstrong held off on the line in Revel by Serhiy Ushakov on stage 13. As the teams headed for the second rest day after stage 14, the highest-placed Motorola rider in GC was Colombian Alvaro Mejia some 26 minutes adrift of Miguel Indurain who was on his way to a fifth Tour victory in as many years.

The Fabio Casartelli Memorial, Col de Portet d’Aspet

Fabio’s death on stage 15 could have been a watershed for safety in professional cycling, not only rider protection (the compulsory wearing of helmets would be a further 8 years away, and in the aftermath of the death of Andrei Kivilev after a crash in the 2003 Paris-Nice) but also course safety. The concrete blocks designed to prevent vehicles plunging over the edge of the Col de Porte d’Aspet also contributed directly to the catastrophic head injuries that Fabio sustained. In some respects, the refusal to address both issues at the time also robbed Fabio of some fitting legacy to the sport he loved.

To some, he may simply be a tragic figure or the invisible team-mate of Lance Armstrong on the road to Limoges. To many others, though, Fabio will remain the grinning young man in the Azure jersey, sunglasses perched atop his ruffled dark hair and a gold medal hanging from his neck. Campione Olympico.

Footnote: Fabio Casartelli would have turned 50 on 16 August 2020. By a twist of fate, Il Lombardia, the one-day Classic which finishes in Castartelli’s hometown of Como, took place the day before. On the steep, fast descent of the Muro di Sormano, Deceuninck - Quick-Step rider Remo Evenepoel misjudged a tight left-hand bend and collided with a low stone wall on a bridge. The impact ejected the young Belgian over the wall and into the ravine below. As medics made their way to attend to the rider lying still in a near recovery position, the cycling world once again held its breath.

Forgotten Yellow: Greg Lemond and the 1990 Tour de France

Thirty years ago this month, Greg Lemond won his third Tour de France and in doing so joined an exclusive club alongside Philippe Thys, Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault.

Thirty years ago this month, Greg Lemond won his third Tour de France and in doing so joined an exclusive club alongside Philippe Thys, Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault. Yet the 1990 edition passes almost unnoticed in the shadow of those famous 8 seconds the previous year and the stress of Lemond’s debut victory in 1986.

In other circumstances the 1990 Tour de France might have been billed as a battle royale between 3 former champions who had between them won the previous 4 editions of the race plus the man who so famously and so cruelly had victory snatched from him on the Champs Elysees the previous year.

Pedro Delgado (Banesto) came into the race having finished second in May’s Vuelta a Espana behind Marco Giovanetti who kicked off a grand tour double for Italian rider that Spring. Stephen Roche (Histor-Sigma) had finished second at Paris-Nice (behind Delgado’s teammate Miguel Indurain) and had won the 4 Days of Dunkirk. Laurent Fignon (Castorama-Raleigh) took top honours in the prestigious Criterium International in March but had abandoned a Giro d’Italia, which was dominated from start to finish by Gianni Bugno. Fignon dislocated his pelvis in a crash on Stage 5 but battled on for another 4 days before pulling out of the race. “The Professor” took the starting ramp at Futuroscope recovering both mentally and physically .

While supported by a Z-Tomasso squad featuring the likes of Robert Millar and Ronan Pensec, Greg Lemond’s spring had been nothing short of wretched. A bout of Epstein-Barr Syndrome had made training nigh-impossible without debilitating fatigue and as a result the American had done precious little racing. The highlight of his Giro had been a 12th place in the Stage 19 time trial on his way to a lowly 105th on GC. A subsequent 10th at the Tour de Suisse a mere fortnight before the Grand Depart didn’t really hint at the American being a major force over the next 3 weeks.

Depart

The opening weekend of the 77th Tour centred on the Futuroscope theme park near Poitiers. Lemond finished second in the Prologue to Thierry Marie (PDM-Concorde) and 20 seconds covered all 4 of the main protagonists. The following day’s Stage 1 saw an early 139km stage during which a group containing the likes to Steve Bauer (7-Eleven), the largely unknown Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Vagabond) and Lemond’s teammate Ronan Pensec was allowed to escape unchecked. With the afternoon team time trial looming, nobody was going to work to pull them back and with Pensec in the group, the Z-Tomasso team was unlikely to be of much assistance. Frans Maassen (Buckler-Colnago-Decca) won the sprint but Bauer would wear the maillot jaune that afternoon. The Big Four and almost everyone else in the field came in some 10m 35s adrift. Following the TTT, Bauer would remain in Yellow while Lemond slipped quietly out of the top 10 as his Z-Tomasso squad could muster only 7th against the clock.

While the race wound its way northeast and then south, the big guns were largely content to let the others do the work with names like Moreno Argentin (Ariostea) and Johan Museeuw (Lotto-Superclub) among those fighting for stages and green jersey points. A crash on stage 3 cost both Delgado and Fignon time but it would ultimately cost the Frenchman his race, abandoning the following day with a calf injury. In his autobiography We Were Young and Carefree, he would describe his “one proud gesture”, unpinning his own race numbers – “a gesture born of disillusion and pride, a way of sticking two fingers up at fate.” Laurent Fignon would not win a third Tour de France.

It wouldn’t be until the longer 61.5km individual time trial on Stage 7 that Delgado and Lemond would next bother the sharp end of the racing, finishing 4th and 5th respectively over 2 minutes behind stage winner, Raul Alcalá of PDM-Concorde. The time trial had been a disaster for Stephen Roche who lost 3 minutes in the final 3km to finish the best part of 5 minutes behind Alcalá.

Standings after Stage 7:

1. Steve Bauer (7-Eleven) 30h 04’49”

2. Ronan Pensec (Z-Tomasso) +17”

3. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Vagabond) +1’11”

——

7. Greg Lemond (Z-Tomasso) +10’09”

Stage 10 would see the first indicators of mountains form on the road from Geneva to the ski resort of St Gervais-les-Baines on Mont Blanc. Delgado’s attack on the final climb clawed back some 19 seconds to Lemond and, in the process, ended a fading Steve Bauer’s week in yellow. The Spaniard finished 7th on the stage with Lemond rounding out a top 10 headed by RMO’s Thierry Claveyrolat. Lemond’s teammate Ronan Pensec was now celebrating the maillot jaune – much to the delight of the home nation and its press - as well as his 27th birthday, while the American was still nearly 10 minutes adrift in 8th place.

Troubling the Podium

The next day offered a tantalising glimpse that a race might just be on. The Cols de la Madeleine and du Glandon merely set the scene for the 182.5km stage to finish atop the Alpe d’Huez. The previous day’s winner, Claveyrolat was first over la Madeleine and led the race over the Glandon. Pedro Delgado then launched an attack that only Lemond, Delgado’s Banesto teammate Miguel Indurain and Gianni Bugno could follow. With Claveyrolat brought back into what was now a lead group, Indurain set a metronomic pace for his leader who – with Indurain’s work for the day done - attacked again at the foot of the Alpe. Lemond and Bugno picked up the gauntlet and as the trio wound its way up the 21-hairpin bends, it was the Spaniard who began to drift off the back just as a trio containing Claveyrolat and Eric Breukink made contact once again. A sharp acceleration by Bugno took the quintet beyond Delgado and on to the summit. It was Bugno and Lemond who would contest the sprint – the American almost overcooking his exit from the final hairpin – and the young Italian would prevail. Ronan Pensec would wear Yellow for a second day, but his team leader was now third in the standings, 9 minutes adrift.

Eric Breukink won against the clock on Stage 12, catapulting himself into third on GC. Behind him, Pedro Delgado would best Lemond by some 26 seconds, narrowing the gap between the protagonists, and Pensec’s 49th place on the road, some 3m 50s behind would cede the maillot jaune to Claudio Chiappucci. While Lemond had lost time to his rival – and a place in the GC standings - he had still gained another 90 seconds on the main prize.

Standings after Stage 12:

1. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Vagabond) 49h 24’08”

2. Ronan Pensec (Z-Tomasso) +1’17”

3. Eric Breukink (PDM-Concorde) +6’55”

4. Greg Lemond (Z-Tomasso) +7’27”

5. Pedro Delgado (Banesto) +9’02”

Stage 13 to St Étienne would be a torrid one for the new race leader. A break containing Delgado, Breukink and Lemond slipped up the road unnoticed and Chiappucci would spend the day isolated and leading the chase. His inattention ultimately cost him the better part of 5 minutes on a day won by ONCE’s Eduardo Chozas who took the sprint from a group that contained the ever-strong Eric Breukink and Lemond. Pedro Delgado finished in the second group, losing every second (and more) of the time he’d gained in the time trial just 72 hours before.

Standings after Stage 13:

1. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans – Vagabond) 52h 49’13”

2. Eric Breukink (PDM-Concorde) +2’02”

3. Greg Lemond (Z-Tomasso) +2’34”

In Pursuit of Glory

The race truly came alive in the Pyrenees and on Stage 16 the riders contemplated a 215km effort from Blagnac to Luz Ardiden that crossed the Cols d’Aspin and du Tourmalet. Chiappucci was still in Yellow but with his lead having been shaved by a few more seconds in each of the previous 2 days simply couldn’t afford a war of attrition. His attack on the Aspin with a group of 6 other riders was certainly brave and could have been fruitless had he not been first over the summit before continuing alone to the Tourmalet, some 3m 20s ahead of the chasers.

From such leads are Grand Tours won and it was Lemond who was forced to lead the high-speed chase on the descent, his group catching Chiappucci before the climb to Luz Ardiden. When Fabio Parra attacked, it was Lemond again who led the chase group – minus an exhausted Chiappucci - and set about taking time from the race leader. Miguel Indurain and ONCE’s Marino Lejarreta went with him, but neither was particularly keen to work with the American. The priority was gaining time so, with Lejarreta distanced in the last few kms, and Lemond having driven the pace from the foot of the climb, it was perhaps no surprise that it would be Indurain who took the stage, jumping from the World Champion’s rear wheel as they exited the last corner.

With the clock ticking, Claudio Chiappucci crossed the line to retain the race lead by a scant 5 seconds. His defence of the Yellow Jersey had been no less heroic than Lemond’s pursuit of it had been relentless.

Standings after Stage 16:

1. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Vagabond) 69h 27’50”

2. Greg Lemond (Z-Tomasso) +5”

3. Pedro Delgado (Banesto) +3’42”

Now within touching distance of the race lead, Lemond came within a whisker of it all falling apart the following day. The final day in the mountains on Stage 17 would see the peloton tackle both the Col d’Aubisque and the Col Marie-Blanque on the road from Lourdes to Pau. On the Marie-Blanque, Lemond punctured as both Delgado and Chiappucci attacked. After a slow wheel change, insult was added to injury as a mechanical then forced a bike change for the American. Staring at a 3-minute deficit to his team leader’s rivals, Z directeur Roger Legeay ordered the group of 4 riders ahead of Lemond to sit up and wait for his arrival. One of the abiding images of this stage is a furious Lemond leading his team off the Marie-Blanque while the 4 riders assigned to pace him back to the lead group hung on. As Alfa Lum rider Dimitri Konyshev became the first Soviet rider to win a stage of the Tour, Lemond would finish in the same group as Chiappucci and Delgado.

With the sprinters contesting Stages 18 and 19, the GC battle would once again come down to an individual time trial, this time around Lac de Vassiviere. Chiappucci was certainly not known for his ability against the clock and so it came to be on the day. Eric Breukink took the stage comfortably from Raul Alcala and Marino Lejarreta with Lemond coming in 57 seconds behind the winner. Chiappucci’s 8 hard-fought days in the maillot jaune came to an end when he finished 2’21” behind Lemond on the road.

Final Standings after Stage 21:

1. Greg Lemond (Z-Tomasso) 90h 43’20”

2. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Vagabond) +2’16”

3. Eric Breukink (PDM-Ultima-Concorde) +2’29”

------

4. Pedro Delgado (Banesto) +5’01”

------

44. Stephen Roche (Histor-Sigma) +1h 00’07”

-----

DNF Laurent Fignon (Castorama-Raleigh)

Reflection

Greg Lemond’s third Tour de France was delivered without a single stage win and with a solitary day in the Yellow Jersey. Nevertheless he describes it as his most enjoyable. By others, the victory is considered as boring or lacking in panache or emotion and yet, having come into the race “uncooked”, Lemond displayed these virtues and more during the 3 weeks.

Before the race, Laurent Fignon told the media that the American “always bases his races on following the most dangerous rider on GC, never attacks and saves himself for the time trials.” This was perhaps born from the bitterness of Fignon’s experience the previous year but while the final result did once again rest upon the results of a time trial, the rest of that statement does not bear scrutiny.

The era of controlling races a la Banesto, ONCE, US Postal or Team Sky had yet to dawn and, while Z-Tomasso had an experienced team in support, it was their leader who took the chase to Chiappucci while distancing Delgado, whether in those kamikaze descents or single-mindedly driving the pace when all may have been lost. Perhaps the anomaly of a 10-minute break on that first road stage had already cast the die for the race but at no point was Lemond playing safe nor limiting his losses. In fact, the Stage 1 result forced exactly the opposite scenario. In doing so, not only was Lemond honouring the proud history of the race but also the Rainbow Jersey of the World Champion in whose rainbow stripes he remains the last man to win the Tour de France.

Footnote: 1990 would be Greg Lemond’s last Tour win and arguably the last edition contested before the dawning of the EPO era. Lemond remains officially the only American to have ever won cycling’s most famous race.